Söze

Hardware mods for my PC, with a suite of software services to make it all run smoothly. The mods include an LCD mounted on the front and a strip of RGB LEDs inside, all driven by a Raspberry Pi Zero.

Background

A long time ago (circa 2013), I decided I wanted to mod my PC. Fortunately, my case (the BitFenix Prodigy) is very amenable to that kind of thing, so I had a lot of options. Over the years, I added stuff, took it away, changed it, turned it upside, and eventually ended up with what I have today: an RGB LED strip, and a character LCD mounted to the front.

The Hardware

The hardware involved in this obviously includes the LEDs and an LCD, as well as a few other pieces that make it possible to control everything from software.

Raspberry Pi Zero

Raspberry Pi Zero W | Adafruit motor HAT

The RPi serves as the brains of the operation. It, along with the Motor HAT expansion board, controls the LEDs and the LCD. It also connects to the computer's power supply to determine when the PC turns on and off (which is used in the software to shift between "day" and "night" mode).

The RPi connects to the PC's motherboard via USB for power, and uses WiFi for network access. But since my PC case is basically a Faraday cage, sometimes the WiFi isn't strong enough and I have to fall back to using the USB as a network interface as well. Generally though, the WiFi is good enough. If you're curious, check out the README for a detailed layout of all the pins being used on the RPi.

LEDs

A simple RGB LED strip. Each component (red/green/blue) is controlled by PWM from a motor controller. This strip can display pretty much any color, but the catch is that the LEDs all show the same color at once. But still, RGB makes your computer faster (as proven by Science™), so this piece is critical. Similarly, I'm currently investigating the effects of flame decals on CPU performance. Early results are promising.

This LED strip has gone through a few iterations, including pure analog control (which involved a homemade heatsink to prevent the whole thing from catching fire) and being driven by an Arduino Uno. This current iteration, with the Raspberry Pi and the motor controller, is definitely the cleanest and most configurable of all though. Having a full blown OS in control means the software can be a lot more complex and can provide a web UI (see UI).

LCD

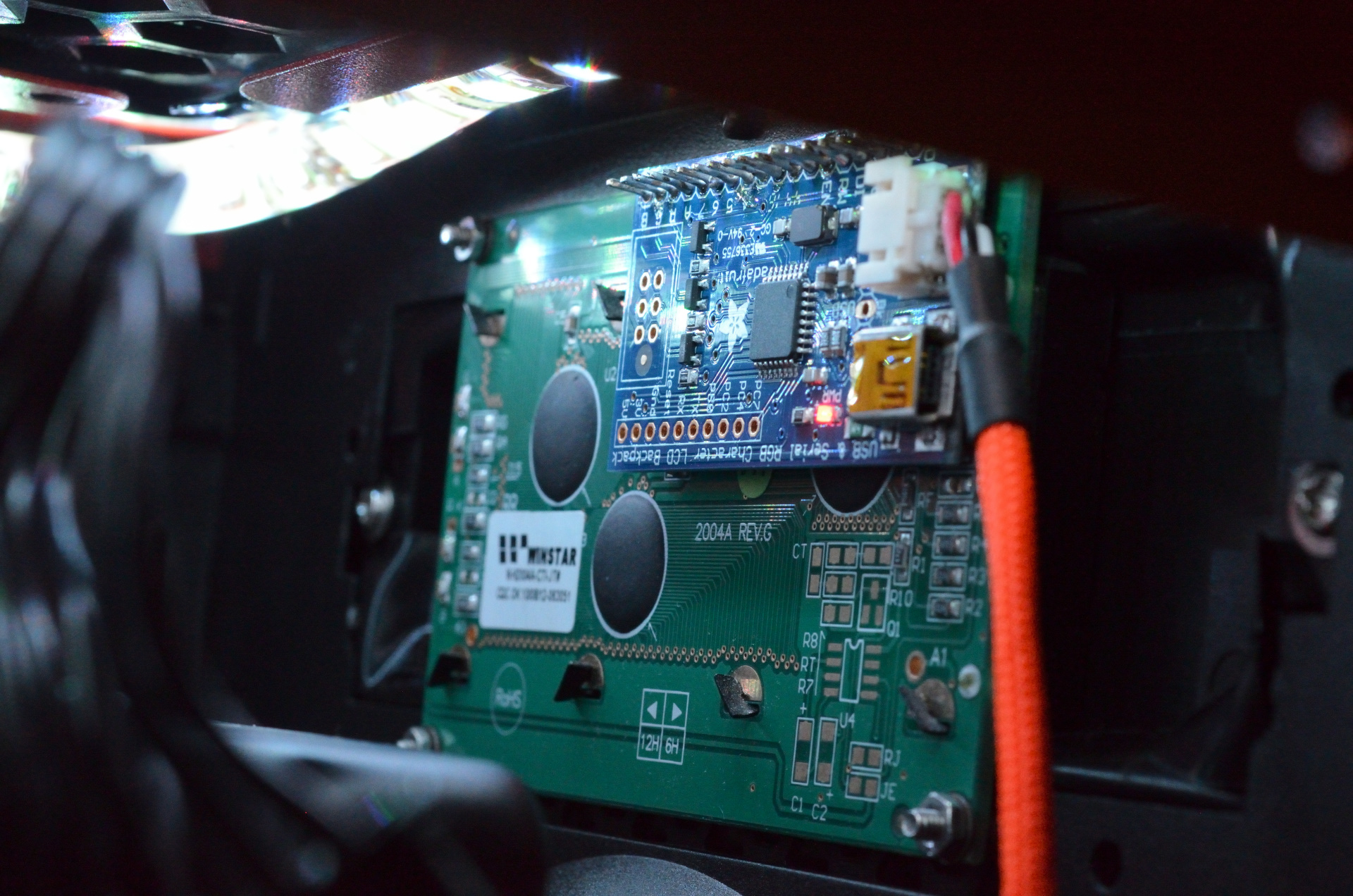

RGB backlight LCD | LCD backpack

This is the more complicated half of the mods. I mounted a 20x4 character LCD onto the front of my PC (in the space intended for a 5.25" CD drive). The LCD supports loading custom characters, which means I was able to define characters that form pieces of bigger characters, which means... big numbers! Wow, computers!

I initially drove this with an Arduino Uno wired directly to the LCD, but then I switched over to the Raspberry Pi and discovered Adafruit's LCD backpack, which cuts a 16-pin wiring operation down to a 3-pin UART connection. It also greatly simplifies the software logic to a basic serial protocol, which makes controlling screen content/color/etc. much easier.

The Software

If the RPi is the brain, then the software is the... braincode? I don't know, this metaphor is breaking down. Software do what software do, it tells the RPi how to function. Each of these four components is a separate body of code, and they all communicate with each other over the network. Here's a synopsis of all the pieces. Basically, the UI talks to the API over HTTP (like and normal web app), then within the server, everything uses Redis as an intermediary.

Redis is great for this application because it's fast, lightweight, handles all the annoying parts of networking, and the pub/sub model makes it easy to notify the other components when something changes. It also provides some basic persistence, which is easier to use than dumping settings to a JSON file and reloading them on startup.

UI

Everyone loves web development, right? This is a pretty simple UI built in TypeScript with React. It gives you full control of the LEDs and the LCD. It's hosted directly of the RPi, which makes deployment easy, but unfortunately means it's only accessible on the LAN. To make it accessible anywhere on the Internet, I'd have to set up a VPN to the RPi, host the UI elsewhere, and figure out auth. That sounds like a lot of work, and why would I want to control the PC while I'm not home anyway?

API

This is a pretty thin layer that provides read/write access to the user's settings via HTTP. It uses Python+Flask. It doesn't involve any auth/permissions/etc., so very simple. For reads, this just reads a JSON string from Redis and returns it to the user. For writes, it basically validates JSON then dumps it into Redis.

Reducer

So if the RPi is the brain and the software is the braincode, then the reducer is the brain's Supreme Metatarsal Cortex (or something like that). Basically, this is the chunk of the code that takes the users settings and constantly calculates what each bit of hardware should be doing. Periodically (e.g. every 10ms), it recalculates the current LED color, and the current LCD text and color, then sends that data to the display.

This communicates in both directions via Redis. It reads user settings from Redis, calculates derived state, then writes that back to different keys in Redis.

The whole system is designed in order to offload all the difficult logic into the reducer. By putting all the complicated stuff in one place, it makes it easy to add and change functionality. And in most cases, changes here require minimal to no corresponding changes in the API/display, because the Redis contracts are decided to be as unrestrictive as possible.

Display

The display is a minimal adapter between the reducer and the actual hardware. The reducer produces an RGB color for the LEDs and a stream of binary commands for the LCD, so all the display has to do is take that data from Redis and forward out over the appropriate hardware channels. It might seem like this job doesn't justify having a completely separate service, but there's a big upside to it: mocking.

When developing and running this on my desktop/laptop, obviously the expected hardware isn't present. After experimenting with a few other mocking mechanisms at first, I found this was the easiest way to do mocking. There is an alternative display that doesn't attempt to interact with hardware at all, and instead just mimics the LED and LCD state in a terminal window. This makes it easy to spin up 90% of the stack exactly how it would exist on the RPi, and minimize the amount of code that has to be mocked.

In Conclusion

So that's like... everything. Hope it was interesting? All the code is on GitHub (the hardware is not). It's taken many years of tweaking but I'm very happy with where this setup is now. I'm sure I'll continue to work on it in the future (currently I'm working on porting chunks of the software to Rust for fun), so it's only going to get better.